The Paradox of ‘Mental Health’

Of all the responses I’ve had when I tell people I work in mental health, one in particular has stuck in mind:

“Ah yes. I know people with mental health. My brother has it, and my friend too.”

I didn’t take the trouble in this particular conversation to point out that the speaker also had mental health. That, by virtue of being alive, every human, indeed every animal, possesses mental health. No less, he struck a chord with the mistaken notion that “mental health” is an illness.

This is a paradox implicit in general public perception of mental health and what it means, no doubt stemming from a disturbing institutionalisation of the term. To clarify my point, when someone says “physical health,” the listener may envision the gym, or a playing field, or a marathon, or their good-looking personal trainer, rather than a lino-floored hospital ward and Nurse Cratchett in One Flew Over the Cuckoos Nest.

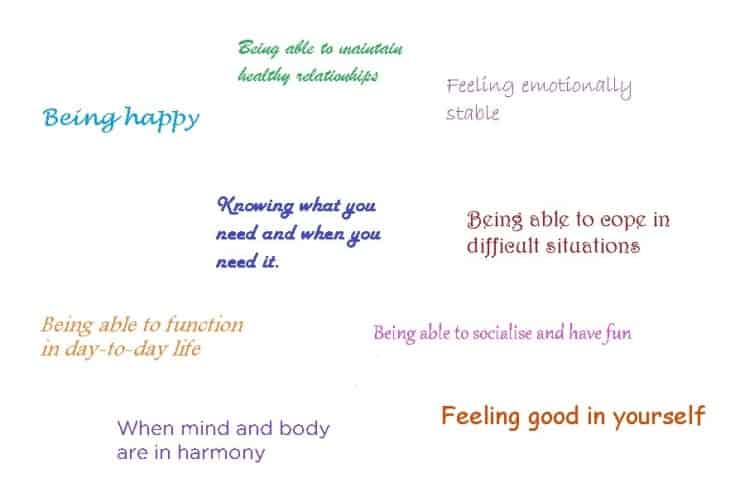

This month, we delivered our new Discovering Good Mental Health course, which aims to dispel such misconceptions around mental health, and what it means to be in good mental health. In the first instance, it asks participants what “good” mental health is. Here are some examples of their ideas:

Being in good mental health constitutes all of the above at one point or another, and also recognises that they are not all of them possible all of the time. Sometimes, we’ll feel bad in ourselves, but be able to function in day-to-day life. Feeling emotionally stable is not to be eternally happy; knowing what you want and when you need it doesn’t mean you’re able to socialise and have fun, and harmony between mind and body doesn’t always orchestrate healthy relationships. In short, “good” mental health is painted like The Brady Bunch, but actually looks more like the Addams Family, the weird and wonderful surrounded by dark and stormy weather, with no pretense to normality.

Discovering this is no walk in the park. It puts into question widespread, deep-seated notions of “happiness” and asks that we identify unhelpful habits we’ve acquired in pursuit of it.

“The time to focus and identify habits I didn’t know I had, is what helped me most on the course,” commented Anne Wylie on the Discovering Good Mental Health course, “now I’ll be able to work to change those.”

In dismantling the paradox that ‘mental health’ is an illness, we can start to explore it for what it really is – a continuum between Brady Bunch and Addams Family. And as long as we accept its idiosyncrasies and inconsistencies, and distinguish what we can change from what we can’t, either one makes a portrait of good mental health.