A Window On Time

“I was posted to RAF Gatow, East Germany, in 1964. Stated purpose: to allow pilots to keep up their flying hours. Real purpose: spying on Russian troops.”

Ken joined September’s Telling Your Story course with a life rich in stories from his years in the RAF. His role had taken him on adventures from Mexico to Malaysia and it seemed mission impossible to express the length and breadth on a single page.

A query we often get is ‘what does Telling Your Story actually involve?’ Admittedly, the title is misleading. It suggests unraveling every event in your life, the good bad and ugly, in the order of their happening. But Telling Your Story is not about that. It’s about exploring which areas of your life you want to tell, and how you want to tell it. It’s about looking at the wealth of memory, emotion and sensory experiences that make us who we are, and using the pen to change our perspective on what they mean to us.

Throughout life, we are told many stories about ourselves: by parents, teachers, doctors, employers, social workers, therapists, counselors, law enforcers – the list is endless. Some of these stories are helpful, some of them are not, but we assume they are true all the same. Telling Your Story is about taking back control of your story in the way that best reflects you.

Ken decided to focus his story on a window in time significant not only to his personal history, but that of Europe’s, writing it up on A3 paper, complete with photographic evidence.

“BRIXMIS,” he explains, “was the British mission to the Soviet’s HQ in Potsdam…” So begins a tale of deceit, negotiation, intrigue, bravery, and the exchange of a bottle of whisky that impacted all our lives. That’s the magic of Telling Your Story – realising how much you’ve achieved, and how intricately this feeds into the stories of others.

Many thanks to Ken for contributing his story. You can read it in full below.

N.B. Ken highlights that he was not personally involved in the BRIXMIS mission but posted as a SAC Radar mechanic, “usually to be found playing bridge on the airfield.”

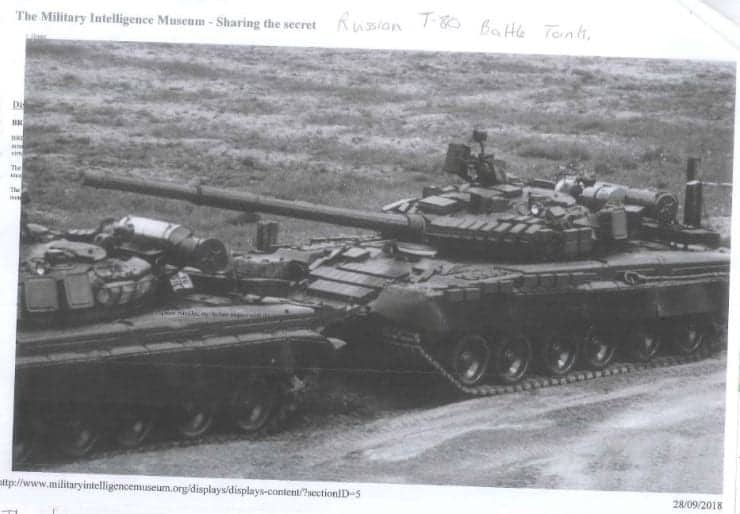

“The above is one photograph of Russian military hardware of hundreds of thousands taken by Brixmis personnel in the German Democratic republic. The T-80 was a multi-fuel gas turbine powered tank, capable of high speeds cross country.

The Stasi were East German secret police, whose architect was Walter Ulbricht, the fanatical East German dictator. Stasi were possibly similar to the Nazi Gestapo: secretive, ruthless and everywhere. They were also supplemented by informers they recruited to spy on their own families and people in the local community. It must have been horrible knowing you were constantly being watched.

The Brixmis were a valued addition to intelligence gathering by the allies during the Cold War. They were there to keep watch in case the Russians mobilised for an attack on Western Europe.

I was posted to the RAF Gatow in November, 1964. I met Ian Wilson on the plane going out there. He was a linguist, speaking Russian and German, who was employed in Hanger 5, which had multiple aerials used to monitor Russian and East German communications.

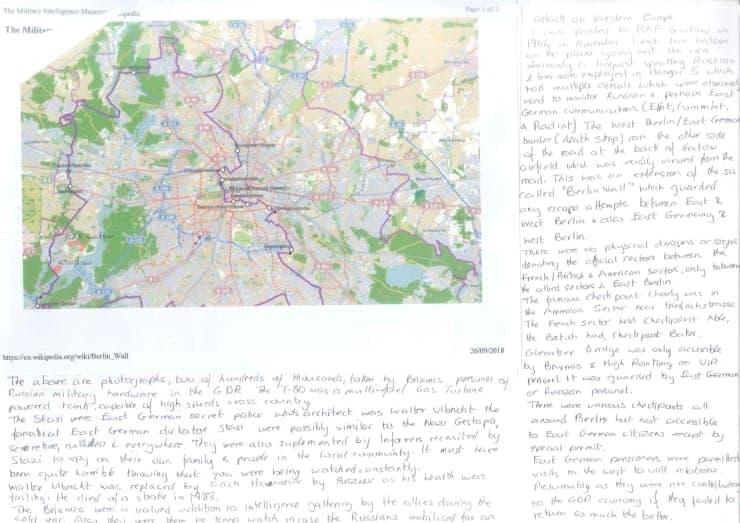

The West Berlin/East German border (death strip) ran the other side of the road at the back of Gatow airfield, and was easily viewed from the road. This was an extension of the Berlin Wall, which guarded against any escape attempts between West Berlin and East Germany.

Though there were no physical signs denoting the official sectors between the French, British and American sectors, there were various check points all around Berlin, which were not accessible to East German citizens. Only East German pensioners were permitted to visit relatives in West Berlin, presumably because they were not contributing to the GDR economy – if they failed to return, so much the better.

BRIXMIS

British mission to the Soviet’s HQ in Potsdam. A Brixmis vehicle spent 5-7 days touring East Germeny, trying to gather intelligence on Russian troops’s movement (of which there were 350,000 in GDR). We would sneak into the woods to observe loading ramps at rail heads, photographing tank motorised guns. Occasionally, an one of our personnel might be captured, resulting in arrest until a senior Russian officer was sent for. The prisoner would be released after a conference and bottle of whisky were exchanged. Still, there were “one or two” deaths from aggressive action by Russian military.

At times, we would lay down the sides of back alleys to photograph Russian military convoys passing, once capturing in detail a new Russian artillery piece, which arrived soon after on President Lyndon Johnson’s desk.

RAF Gatow’s stated purpose: to allow pilots to keep up their flying hours. Real purpose: spying on Russian troops.”